"On the same day separated by 34 years, one inventor revolutionized agriculture in the fields above, while another changed how we see beneath the waves."

🌾 June 21, 1834: Cyrus McCormick Patents the Mechanical Reaper

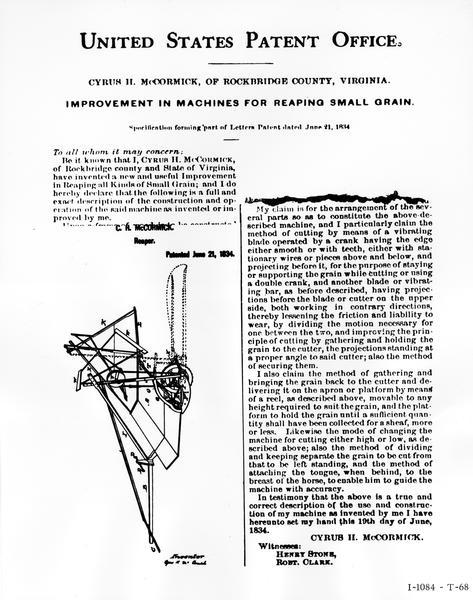

Imagine toiling for days to harvest a single acre of wheat—then suddenly, a horse-drawn contraption swoops in and finishes it in a fraction of the time. That was the promise of the mechanical reaper patented on June 21, 1834, by Cyrus Hall McCormick of Virginia.

This marvel of 19th-century engineering changed agriculture forever, transforming it from manual labor into mechanized industry.

📜 Cyrus McCormick’s mechanical reaper drawing, 1834. (Credit: Wisconsin Historical Society)

The reaper used a combination of a toothed cutting bar, a reel to guide the stalks, and a platform where the grain could be collected—all drawn by horses. The design was deceptively simple but allowed one person to do the work of five.

🔧 What Made It Revolutionary?

- Speed: Harvesting an acre dropped from 20 hours to 2.

- Scalability: Farmers could plant more crops knowing they could harvest them.

- Economic impact: Sparked the rise of commercial agriculture across the U.S.

McCormick's machine would eventually form the foundation of the International Harvester Company—a titan of 20th-century agriculture.

📜 Patent Drama? Oh Yes.

While McCormick became the face of mechanized farming, inventors like Obed Hussey filed similar patents, leading to lawsuits and rivalry. Even a fire destroyed McCormick's factory in Chicago. But like any good inventor, he plowed ahead.

🌊 June 21, 1868: Sarah Mather Patents the Underwater Telescope (Bathyscope)

Fast forward 34 years. On June 21, 1868, Sarah Mather of Brooklyn was awarded a U.S. patent for a curious device: an underwater telescope, also called a bathyscope.

Before submarines or scuba masks, her invention allowed people to observe underwater from the safety of dry land—or at least the deck of a boat.

The bathyscope was a long tube with a lens and a watertight glass seal at the bottom, allowing users to look below the water’s surface without submerging themselves. It was used in ship inspections, harbor surveillance, and even the recovery of sunken objects.

🌟 Why Sarah’s Invention Mattered

- Innovative optics: Allowed underwater viewing without diving.

- Maritime utility: Useful in ports and for naval operations.

- Pioneer status: She was one of the few women granted a U.S. patent in the 1800s.

Though less famous than her male peers, Sarah Mather’s work laid the foundation for later underwater exploration—from Jacques Cousteau to ROVs exploring the Titanic.

⚖️ Dual Legacy: Fields and Oceans

So what do a field-harvesting machine and an underwater viewer have in common?

Both inventions allowed humans to interact with the natural world in new, efficient ways—one by conquering land, the other by peering into hidden marine spaces. One fueled food production. The other opened up the unknown.

Also worth noting: Cyrus McCormick became a business mogul. Sarah Mather? Barely a footnote in history books. A perfect example of innovation’s unfair gender gap.

😄 Fun Fact Interlude

- McCormick’s machines were so effective that by the 1850s, they were shipped worldwide—sort of the Amazon Prime of agriculture.

- Mather’s bathyscope predates Jacques Cousteau’s diving mask by nearly a century. Take that, Jacques!

🧾 TL;DR Summary

- June 21, 1834: Cyrus McCormick patents the mechanical reaper, changing agriculture forever.

- June 21, 1868: Sarah Mather patents an underwater telescope, pioneering marine observation.

- Big picture: Two inventors. Same date. Very different legacies—equally impactful.

📣 Join the Conversation

Would you rather revolutionize farming or explore the sea? Have you seen a bathyscope or an old reaper in real life?

Leave a comment: Which June 21 invention speaks to you most?

📚 Sources

- Wisconsin Historical Society – McCormick Reaper Drawing

- National Inventors Hall of Fame – McCormick Bio

- Google Patents – Sarah Mather Patent

- Various entries from Britannica and U.S. Patent Office archives

Comments

Post a Comment